The Old Swede: August 6th, 2025

Gentleman in the Field: A Life Measured in Miles Walked, Dogs Led, and Meals Earned

Driven vs. Upland

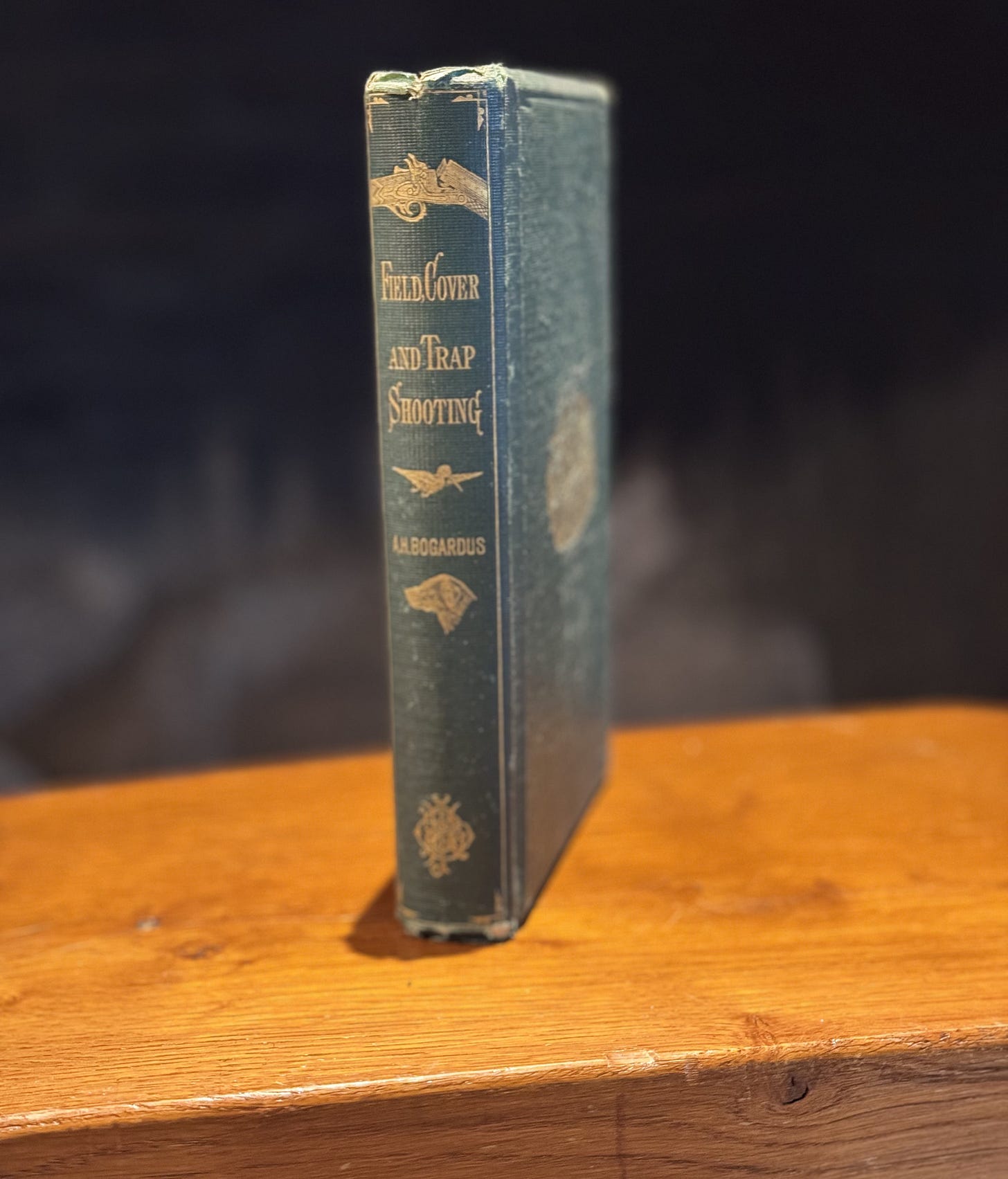

A.H. Bogardus and the Field Shooting of 1874

In Field, Cover and Trap Shooting (1874), Capt. A.H. Bogardus recounts the thrilling difference between two modes of sport: the structured drama of field shooting and the intuitive poetry of upland cover work. Bogardus, known as a trick shot and field expert, understood that clay pigeons and live birds demanded different sensibilities—but that the habits learned in upland pursuit trained a sharper eye.

He wrote: “The cover hides more than birds—it conceals your errors.” Upland hunting, unlike driven shooting, demands close reading of terrain, the breath between wingbeats, and a bond with your dog that’s earned, not assigned. A grouse bursting from alder thickets offers no second chances, no loader, and no applause.

In contrast, driven shooting—with its butts, beaters, and coordinated rhythm—represents pageantry and precision. The Gun must read sky angles, wind, and etiquette, often executing shots under watchful eyes. Bogardus respected both. But his heart belonged to the woods.

Recommended Reading

A.H. Bogardus, Field, Cover and Trap Shooting (1874)

Manners Maketh Man

A Lost Bird is Still Yours

Among the enduring principles of field sports, none is more telling of a sportsman’s character than how he handles a missed or wounded bird. To some, it’s out of sight, out of mind. To a gentleman, it’s part of the day’s tally—an unspoken promise made at the shot.

If you down a bird, and it’s not retrieved, you do not shoot another in its place. You work to recover it, call in the dog, or mark its last flight with conviction. This sense of accountability, of stewardship over what you shoot, separates the showman from a gentleman. The limit is not simply a number; it is a moral contract with the game and the ground.

To ignore a lost bird, or leave the the area for someone else to pick up after you, is a breach of field ethics. Praise the dog who recovers it hours later. Thank the guide who never gave up. And if it’s not found, note it in your logbook—because it counts, it’s yours.

Recommended Reading:

Michael Yardley, Shooting Etiquette

T.W. Fenton, The Unwritten Rules of the Field

Kit Review

The Filson Tin Cloth Strap Vest

No piece of upland gear better bridges function and tradition than the Filson Strap Vest. First introduced in the early 20th century and continually refined, it remains a staple for quail woods, prairie walks, and rugged thickets. Why? Simplicity.

Two roomy shell pockets are placed for easy access. The rear game pouch, built of abrasion-resistant tin cloth, handles a brace of birds and folds flat when not in use. The shoulder straps and belt offer adjustability over layers—from summer canvas to winter mackinaw. The waxed finish sheds briars, rain, and pine sap. And perhaps most importantly, it wears in, not out.

Unlike synthetic vests with plastic zips and neon piping, the Filson strap vest honors restraint. It doesn’t proclaim; it endures. It’s also unrestrictive, making it ideal for wearing over heavy flannel shirts on cool mornings.

If it’s handed down one day, it’ll carry stories in every crease.

Shop Filson Tin Cloth Strap Vest

Recommended Reading:

Filson Catalog Archives, Seattle Public Library (c. 1930–1950)

Spirit of the Week

William Larue Weller — A Damn Good Bourbon

From Buffalo Trace’s revered Antique Collection, William Larue Weller bourbon stands tall—uncut, unfiltered, and unforgettable. Named for the pioneer who championed wheated bourbon mash bills in the 19th century, each bottle is a full-bodied tribute to complexity.

Expect a nose of dark cherry, toasted oak, and baking spice. On the tongue, there’s a crescendo—vanilla, caramel, cinnamon, and pipe tobacco—with a long, warm finish. It’s usually bottled north of 125 proof, yet drinks smoother than expected.

What sets it apart isn’t just the rarity (allocation is fierce), but the sincerity. Weller isn’t dressed up with gimmicks. It’s built like the best shotguns—on feel, balance, and craftsmanship. Poured after a day afield, it speaks in low tones and slow sips.

A flask of Weller in the field would be bold. Best saved for the porch, with boots off and stories in the air.

Recommended Reading:

Buffalo Trace Distillery: William Larue Weller Release Notes (2023)

Pub Spotlight

Fraunces Tavern, New York City

At the corner of Pearl and Broad Streets in Lower Manhattan stands Fraunces Tavern, the oldest surviving building in the city and the most storied bar in American shooting culture—at least if one measures heritage in grit and grace.

Opened in 1762, it was here that General George Washington bid farewell to his officers in 1783. Today, surrounded by skyscrapers and brokerage towers, it offers shooters and statesmen a warm draw of history. The bar pours classic American bourbons, Hudson Valley ciders, and hearty fare like bison shepherd’s pie and duck fat cornbread.

Inside, the oak-paneled dining room echoes with the history of militias, duels, and gentlemen who believed in liberty and good rye. Hunters visiting from Long Island preserves or upstate duck camps often stop here—a final toast to a bird, a dog, or a friendship.

It’s not a shooting pub in the British sense. But it's our kind of place—where leather smells meet barrel talk.

Recommended Reading:

Fraunces Tavern Museum Archives, NYC Historical Society

Driven & Upland

Tales from the Grouse Woods

There’s something sacred in the rustle of a grouse slipping through mountain laurel before it breaks cover. The old-timers speak of it with reverence—a mix of dread and delight—as if the bird itself were part spirit, part feather.

Grouse hunting isn’t about limits. It’s about limits tested. The walking is hard, the shots quick, and the cover never quite friendly. But that’s the beauty. Each flush is a heartbeat. Each missed bird a lesson. Each dog cast through aspen stands a story.

In the Allegheny highlands, the Maine Northwoods, and the frost-bitten hills of the Upper Midwest, there live men and women who return every autumn—not for trophies, but for the test. For the bell collar gone silent. For the flight you never saw. For the hope that next time, you’ll swing just a second faster.

And sometimes, if you’re lucky, you’ll walk out with one bird in the bag—and an entire season in your memory.

Recommended Reading:

Tom Huggler, A Fall of Woodcock

George Bird Evans, The Upland Shooting Life

Burton Spiller, Grouse Feathers