The Old Swede: August 1st, 2025

The World Beyond the Gunroom: A dispatch from the borderlands of adventure, elegance, and enduring field tradition.

Off-Road Well

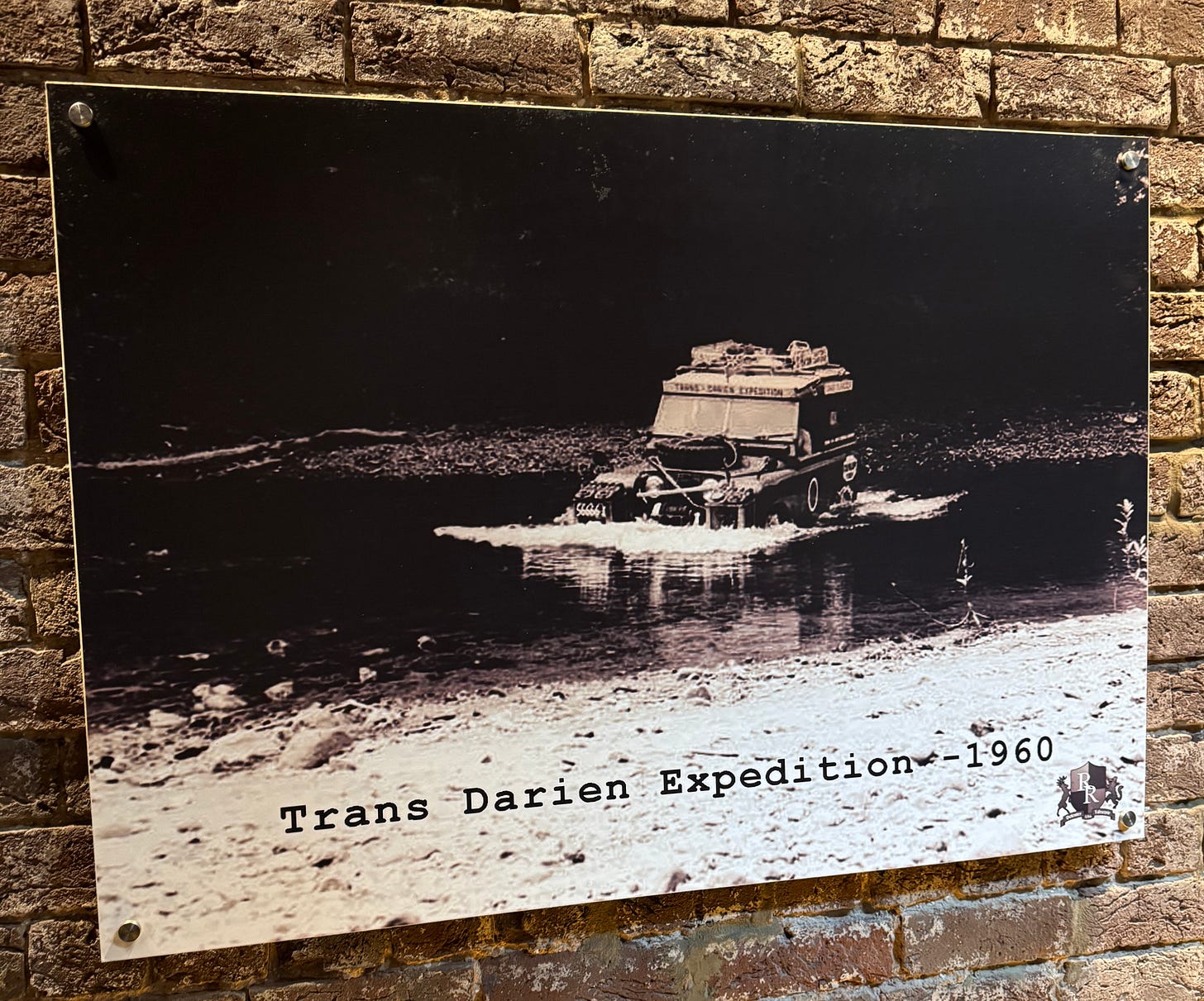

The Trans-Darien Expedition of 1969 — Where Land Rovers Met the Impassable

In 1969, a British-led expedition set out to do what no one had achieved before: drive the full length of the Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. But between Panama and Colombia lies the Darien Gap—100 miles of jungle, swamp, and mountainous terrain considered unpassable by vehicle.

The expedition was led by Major John Blashford-Snell, a Royal Engineer, and relied on two specially outfitted Land Rover Series IIs. Winches, machetes, rope bridges, and even rafts were employed to move forward, inch by inch. At times, indigenous Embera guides were the only thing keeping them alive.

This crossing wasn’t a PR stunt—it was part of a Royal Geographical Society mission combining diplomacy, science, and grit. It took 99 days to cross the Darien. One Land Rover had to be rebuilt three times. But the expedition proved something more enduring: that British overland travel, when done with courage and logistics, could conquer even the planet’s most formidable obstacles.

Suggested Read:

Where the Road Ends — John Blashford-Snell

London Best

Dukes Bar — The Martini Canon of St. James’s

Tucked away on a side street near Green Park, Dukes Bar inside Dukes Hotel is more than just a cocktail lounge—it is a ritual in restraint. Here, martinis aren’t shaken or stirred behind a bar. They are wheeled to you on a polished trolley, then assembled tableside by white-jacketed bartenders with a reverence typically reserved for Mass.

The gin is frozen. The glass is frozen. The vermouth is misted, not poured. Two martinis per guest is the unspoken rule—any more and you’ll be dining with ghosts. Ian Fleming was a regular. His Bond martinis may have been inspired right here, where No.3 London Dry Gin and Amalfi lemon peel meet in whisper-smooth precision.

The room is velvet quiet. Gentle lighting, oil paintings of empire, and the sound of old money being very still. If your tailor drinks anywhere in London, it’s here.

Read more about London’s Finest Martini

Suggested Read:

Shaken: Drinking with James Bond & Ian Fleming — Edmund Weil

Art & Ephemera

A Stag Shot by John Brown — Fife Arms, Braemar, 6 October 1874

Displayed in quiet reverence at the Fife Arms Hotel in Braemar, A Stag Shot by John Brown is a pencil and watercolour sketch attributed to H.M. Queen Victoria. Rendered on J. Whatman Turkey Mill paper and dated 6 October 1874, the work is delicate yet emotionally weighty.

It depicts a single moment: a red stag, shot by John Brown, the Queen’s Highland ghillie and confidant. There is no flourish, no drama—only observation of what was harvested. Victoria had taken to sketching as a child, but in the Highlands it became her private language. Here, she captures not sport, but memory.

The use of minimal wash, pencil detailing, and faint white touches lends the image a calm serenity. It is art not for display but for reflection and honor.

Now part of the Fife Arms’ extensive collection, the sketch reminds guests not just of royalty, but of the quiet intimacy of the field.

Suggested Read:

Queen Victoria’s Highland Journals

Gamekeeper Journal Entry

The August Watch — From the Ledger of Duncan MacLeish, Glen Garroch, 1932

"Rain drove hard at the north slope. Found stoat sign in the fescue. Moved poults back to the birch fence. Young gundog 'Moss' held steady on two flushes. Mr. D. arrives with guests Saturday — four guns. Prepare beat lines and call on the lads."

So reads a page from the August 1932 gamekeeper’s ledger of Duncan MacLeish, a lifelong keeper at Glen Garroch, on the edge of the Cairngorms. His handwritten ledgers—collected over four decades—speak with the clarity of experience: notes on predators, birds, wind, dogs, and beaters, written in tight, precise cursive.

August was the sharpening month. The grouse were wild and fast, the boys not yet fully broken in, the traps needing oil. MacLeish often annotated his pages with drawings—snare layouts, burn crossings, even wind arrows for each beat.

Today, Glen Garroch’s new owners still walk those beat lines. MacLeish’s name is etched on the bell at the dog kennels, and his journals are kept in an archival box beside the gunroom. His life, like so many keepers’, was never public—but it left a map.

Suggested Read:

The Gamekeeper — Ian Niall

British Campaign Lore

The Safari Camp — Elegance Under Canvas

British expedition life in the 19th and early 20th centuries was defined by what one could pack—and unpack. In this, campaign furniture was the linchpin between savagery and civility.

At safari camps from the Serengeti to the Sudan, officers and sportsmen unpacked Roorkhee chairs, collapsible washstands, dispatch boxes, and folding cots with brass fittings and mahogany frames. These weren’t luxuries—they were necessities of class and order. They turned a tent into a drawing room.

The Roorkhee chair, used by both the British Army and great white hunters, was the backbone of the safari lounge. The campaign chest became dressing table, gun rack, and drinks cabinet in one. Collectors today pay dearly for pieces stamped “Ross & Co.” or “Army & Navy Stores Ltd.” Original campaign trunks, outfitted with compartments for cigars, decanters, and cartridges, still turn up in Kenya, India, and the Scottish Borders.

For the modern gentleman, a well-appointed field room or safari bar isn’t complete without one. They bring history with them—folded, portable, burnished by stories.

Suggested Reads:

British Campaign Furniture: Elegance Under Canvas — Nicholas Brawer

Shooting Estate or Club Invitation

A Highland Stag — The Ghillie’s Gift at Glenfeshie

In the Scottish Highlands, stalking red deer remains the purest form of sporting pilgrimage—a day spent with ghillies who speak not in words, but in glances and wind signs. Nowhere is this tradition better preserved than at Glenfeshie Estate, a jewel of Cairngorms conservation.

The day begins in silence. No vehicles. Just boots, sticks, optics, and steady legs. The ghillie leads; the rifle follows. Across burns, through fescue, along the skyline where stags stand watching like ghosts in the mist. The approach is hours long. A shot is never guaranteed.

At Glenfeshie, the sport is secondary to the balance of the land. Deer numbers are managed to restore ancient woodland. Native pine and juniper return. The ghillies, often from families who have worked these hills for generations, are keepers not only of game—but of Gaelic memory.

A successful stalk ends with a dram beside the beast and perhaps a pony from the forest line. You don’t just shoot a stag here. You earn it.

Suggested Reads:

The Stag and the Rifle — Richard Prior